About The Centre for Cultural Studies

The Centre for Cultural Studies (CCS) was established in August 2014 by the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) within the Department of Cultural and Religious Studies (CRS), replacing the Centre for Culture and Development (established in November 2008). The aim of the Centre is to serve as a platform for the promotion of research activities in the field of cultural studies.

News

The 6th ANCER Conference – Shaping Asia’s Creative Futures: Cultural Relations, Technologies, and the Commons

The 6th ANCER Conference Shaping…

The Society for Hong Kong Studies Annual Conference 2025-Annual Conference 2025

Mobility AND NORMALCY We are…

藝界指康署停行政人員培訓資助 協會理解財赤稱可惜 倡牽頭鼓勵商界贊助

【香港中文大學文化管理專業應用副教授林國偉接受明報的採訪報道】 【明報專訊】康文署為培育藝術行政人員,自2010/11年起分別自行或資助伙伴藝團聘請見習員。本報發現,康文署轄下見習員職位皆列為「空缺」而未見招聘,受惠藝團亦確認署方已停發撥款。香港藝術行政人員協會主席錢敏華表示,計劃孕育不少行內中堅,認為若「因政府沒錢而取消,也挺可惜」,盼當局牽頭鼓勵企業贊助延續計劃。有學者建議,政府可藉重整資助計劃的契機,思考培訓人才的方向。 明報記者 葉希雯

As 2 Hong Kong art spaces seek new leaders, experts weigh in on the impact

In a recent interview with…

Explore all our events which interest you.

International Conference-Creativity and Climate Crisis: Asian Media and Arts in the Anthropocene

Date: 19-20 May 2025 (Mon-Tue) Day 1 / 10:00-16:00 Day 2/ 15:00-19:30 Venue: YIA LT2, Yasumoto International Academic Park, CUHK…

Dialogues in Research: Norms and Deviations

Dialogues in Research: Norms and Deviations Date: 15 May 2025Time: 2:30-6:00pmVenue: LT3, Chen Kou Bun Building, CUHK Registration: https://cloud.itsc.cuhk.edu.hk/webform/view.php?id=13708091 Session 1:…

Global Dialogue in Culture and Art: Curatorial Knowledge, Diplomacy, and Policy

This series of research dialogues brings together scholars from the Institute for Cultural Practices (ICP) at the University of Manchester…

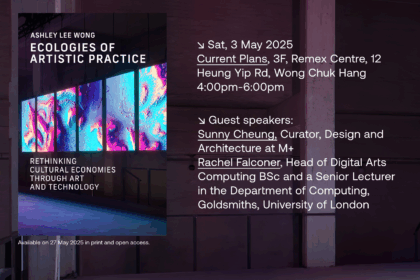

Book Talk: Ecologies of Artistic Practice- Rethinking Cultural Economies through Art and Technology (The MIT Press, 2025)

Book Talk Ecologies of Artistic Practice Rethinking Cultural Economies through Art and Technology (The MIT Press, 2025) by Ashley Lee…

Research and Other Projects

Impact Case Studies: Art and Social Change

Principal Investigator: Prof. LIM Kok Wai, Benny

2021-2024

Funding Source: Project Impact Enhancement Fund (PIEF), CUHK

Funding Amount: HKD 210,000

Project abstract:

This project will focus on arts for seniors and apply the research outcomes to specific projects in collaboration with an arts organization working with seniors in Hong Kong. The project has launched an open-access book project titled, Empower Arts, Animate Communities (co-edited by Benny Lim and Oscar Ho) in October 2021. The book documents all six editions of the Forum on Community Arts organized between 2014 and 2020. The comprehensive documentation includes the rationale of each forum and the summaries of the keynote speeches. Besides the documentation, the book has also included 13 new articles written by international scholars/practitioners on community arts. The project also led to the organization of two forums on art and social change in May 2021 and March 2022 respectively, where participants share their current practice and research on community arts as well as arts and ageing. The project will proceed to develop and document impact projects between 2023 and 2025.

Click here for details: https://communityarts.crs.cuhk.edu.hk/

“Bullet Screen” for Virtual Teaching and Learning: An Innovation for Online Collaborative Video Analysis

Principal supervisor: Prof. TAN Jia

Co-supervisors: Prof. CHUNG Peichi, Dr. LI Tiecheng

Sep 1, 2021 to June 30, 2023

Funding Source: Funding Scheme for Virtual Teaching and Learning, CUHK

Funding Amount: HKD 300,000

Project abstract:

The goal of this project is to develop and implement an online tool for video analysis as a virtual teaching and learning activity using the innovative function of “bullet screen”. Bullet screen, or danmu (彈幕), is a popular function in Asian video sharing websites where users can submit, view, and add textual commentaries flying in and out of screen like bullets while watching the videos online. The bullet screen as a learning tool enables students to watch the video at one’s own pace, pause anytime, and make comments in a virtual setting. Furthermore, it is designed to optimize collaborative online learning with video by encouraging interactions among students and between students and teacher while watching the videos as well as during face-to-face teaching by facilitate in-depth discussions of what was watched. The students can upload videos for others to comment on, which engages students to be partners in teaching and teaching development. As videos are increasingly effective across science, engineering, and humanities, this project serves as a pilot study that has the potential to be adopted by other courses university-wide for future uses. Ultimately, this project aims to develop a learning tool with bullet screen functions which is optimal for virtual as well as mixed-mode teaching and learning.

Click here for details: https://www.cuhk.edu.hk/proj/bulletscreen/